The unscientific enterprise called the Social Cost of Carbon (SCC) is a thinly disguised political attempt to justify some kind of a “carbon tax”. Of course calling it a “carbon tax” or the “social cost of carbon” is doublespeak, or perhaps triplespeak. It is doublespeak because the issue is carbon dioxide, not carbon. What they are talking about taxing is not carbon but CO2. (In passing, the irony of a carbon-based life form studying the “social cost of carbon” is worth noting …)

It is triplespeak because in the real world what this so-called “carbon tax” means is a tax on energy, since the world runs on carbon-based fossil fuel energy and will for the forseeable future.

This energy tax has been imposed in different jurisdictions in a variety of forms—a direct carbon tax, a “cap-and-trade” system, a “renewable mandate”, they come in many disguises but they are all taxes on energy, propped up by the politically driven “Social Cost of Carbon”.

I’ve written before about how taxes on energy are among the most regressive taxes known. Increasing fuel prices hurt the poor more than anyone, because the poor spend a larger fraction of their income on energy. Gasoline prices to drive to work don’t matter to the wealthy, but they can be make-or-break for the poor.

However, in addition to harming the poor, there is a deeper reason that such a tax on energy is a very bad idea.When you tax energy, you are taxing an input to wealth production. Taxing any of the inputs to wealth production is destructive. Instead of inputs, you want to tax the outputs of wealth production. Let me lay out the several reasons why.

I’ve discussed in the past that there are three and only three ways to create real wealth. By real wealth I mean the actual stuff that we use—houses and food and cars and clothing and nails and fish. Real wealth. Here are the three ways to create wealth:

First, you can manufacture wealth—you can build a shirt factory, manufacture a new medicine, or sew clothing in your living room and sell it on the web.

Next, you can grow wealth—you can cultivate an apple tree, keep a home garden, or plant a thousand acres of corn.

Finally, you can extract wealth—you can drill for oil, dig for gold, or fish for trout in a mountain stream.

Everything else is services. Important services to be sure, life-and-death services in some cases … but services nonetheless.

To understand this distinction between services on the one hand and wealth generating activities on the other hand, let me use an example I’ve given before. Suppose there are two couples on a tropical island. One person fishes, one has a garden, one gathers native medicines and building materials from the forest, one builds huts and makes clothes from local fiber. They could go on for a long time that way, because they are creating real wealth. They have food and clothing and housing, the things that we need to survive and thrive.

Next, suppose on a nearby tropical island there are two other couples. On that island one person is a barber, one is a doctor, one is a journalist, and one is a musician. Noble occupations all, but services all … those folks will have nothing to eat, nothing to wear, nothing to keep the rain off. None of those occupations create any real wealth at all, while all the activities on the first island do create real wealth.

This means that if we want our country to be wealthy we need to do everything we can to encourage manufacturing, agriculture, and extraction. And that brings me back to the subject of this essay, the energy tax masquerading as a “carbon tax” and crudely propped up by the laughable “Social Cost of Carbon”.

Let’s set aside for the moment the question of whether a given tax is used wisely or not. And let’s also set aside the consideration of WHAT we tax. Instead, let’s look at the effects of WHERE in the economic cycle we apply our tax.

Each of the three ways to earn wealth has both inputs and outputs. For example, I’ve worked a lot as a commercial fisherman, an extractive industry. The inputs to this way to generate wealth are a boat and motor, nets, diesel, a captain, and some deckhands. The output is yummy fish.

Similarly, the inputs to manufacture are things like raw materials and labor and energy and machinery. The outputs are manufactured goods.

In the third and final way to create wealth, inputs to agriculture are things like water and seeds and fertilizer and tractors and diesel and farmers and field workers. The outputs are fruits and vegetables and fiber and oils and all the rest of the things we grow.

So let me pose you a theoretical question. Assuming that we need to tax the wealth generating process … is it better to tax the inputs to the process, or to tax the outputs of the process?

The answer is perhaps clearest in the field of agriculture, where the question becomes:

Should we tax the seed corn, or should we tax the resulting corn crop?

The first and most obvious reason that we should tax the corn crop is because taxing the seed corn makes it more expensive, and thus it discourages people from planting. We don’t ever want to do that. Discouraging the generation of wealth weakens the economy. We want to encourage the generation of wealth.

The second reason not to tax the seed corn is that agriculture, like all ways to generate wealth, has a multiplier effect. Every single corn seed will likely turn into a plant yielding hundreds of corn seeds. Taxing the seed corn means a farmer can buy less seed … and a reduction of one seed can reduce the eventual crop by a hundredfold. This damages the economy in a second and distinct way.

Finally, there is a third separate hidden damage from taxing the seed corn instead of the corn crop. Having grown up on a remote cattle ranch I know that farmers are broke in the spring and generally only have cash when the crop comes in. The same is true of most wealth generating activities. Money is scarce at the start of the process and ample at the end. This means that extracting the dollars by taxing the inputs to the wealth generating activities puts a much greater strain on the individual wealth generators, the farmers and the fishermen, than does extracting the same dollars from the outputs of the process.

From these three separate kinds of damage it is clear that taxing the inputs to wealth generating activities is generally a mistake.

And this brings me back again to the question of taxing energy. The problem is that energy in the form of fossil fuels is an input to all forms of large-scale wealth generation. This means that driving the cost of energy up for any reason, or in any manner, imposes a greatly magnified cost on the economy through at least the three separate and distinct mechanisms I listed above.

And this is the reason that I am utterly opposed to any kind of tax on energy, whether it is a so-called “carbon tax”, a “renewable energy mandate”, or any other measure to increase energy costs. We have businesses fleeing California for neighboring states in part because our laws REQUIRE that we pay astronomical costs for electricity from expensive green power sources.

When I was a kid, my schoolbooks were clear that cheap electricity was the savior of the poor housewife and the poor farmer. And growing up on a remote cattle ranch where we generated our own electricity, I could see as a kid that it was absolutely true. Having ample cheap electricity transforms a family, a farm, a town, or a society.

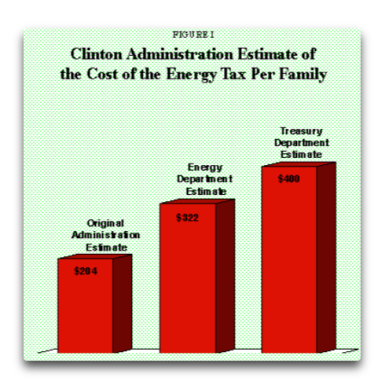

But now, based on the crazy war on CO2, people are doing everything that they can to drive the cost of energy up. Obama’s Energy Secretary famously said he wanted US gasoline (petrol) prices to go up to $8 a gallon like in Europe. Obama himself said that his electricity policy would necessarily cause electricity prices to “skyrocket”. We were into this nonsense all the way back to Clinton.

Let me recap. In addition to energy cost increases hitting the poor harder than anyone, taxing or increasing prices of any of the inputs to wealth generation also damages the economy in three separate ways.

First, taxing or increasing the price of the seed corn discourages planting.

Second, taxing or increasing the price of the seed corn has a very large effect because of the multiplicative power of wealth generation. Since each corn seed can become a plant that produces hundreds of kernels of corn, anything affecting the seeds has a disproportionately large effect on the eventual production.

Third, taxing or increasing the price of the seed corn hits the producers when they have the least money to pay the tax.

Now, consider the role of energy in this process. For all three wealth-generating activities, energy is an input. And this in turn means that any increase in energy prices reduces wealth generation by more, sometimes much more, than the price increase would suggest.

==================

Let me move to a final topic, the size of the claimed Social Cost of Carbon. Estimates range from a “negative cost”, or what ordinary humans would call a “Social Benefit of Carbon”, through net zero cost to a cost of fifteen hundred dollars per tonne. Let me take eighty dollars a tonne as a representative price for the following calculations.

In 2016, humans emitted on the order of ten gigatonnes (10E+9 tonnes) of carbon in the form of CO2. At eighty bucks a tonne, that works out to about $0.8 trillion dollars per year. Since the global GDP (the value of all goods and services produced) is about eighty trillion dollars per year, supporters of a carbon tax have pointed out that if we taxed all emissions that is only one percent of GDP. They say that this is a small price to pay.

But this is a simple view that ignores several important things.

First, the critical metric is not GDP. It is GDP growth. GDP growth averages something around 3% per year. This continued growth is critical both to provide for the needs for an increasing population as well as to providing for lifting the global population further out of poverty. A drag of one percent on the economy reduces growth by a third.

Next, the carbon tax itself would be somewhere around 1% of GDP or less … but that doesn’t allow for the multiplier effect of taxing energy. Because energy is an input to all forms of wealth generation, for all the reasons discussed above the cost to the economy of taxing an input to all wealth generation is much larger than just the size of the tax itself.

Finally, the magic of compound interest and the “rule of seventy”. At three percent growth per year, the “rule of seventy” says that the economy will double in size in 70 / 3 = 23 years. But if we foolishly impose a carbon tax and it drags economic growth down by only a single percent, at 2% growth it will take 70 / 2 – 35 years for the economy to double in size. And since all of these CO2 fears are a long ways out, fifty or a hundred years, over time the small drag of a carbon tax on the economy will loom large.

All of this leads us to a simple conclusion. Even if you wish to fight the eeeeevil scourge of CO2, increasing the cost of fossil fuels is the wrong way to go about it. The associated present and future damage from increasing energy costs, both to the poor and to the economy, far outweigh any possible future benefits fifty years from now.

Now me, I see no reason to fight CO2. I don’t think CO2 is the secret temperature control knob of the climate. No persisting complex natural system is that simply controlled.

But if you do want to fight CO2, DON’T RAISE THE COST OF ENERGY. If you raise energy costs in any manner you are fighting CO2 on the backs of the poor housewife and the poor farmer, the very people you are claiming you are helping. And it’s not just the poor you are hurting. If you raise energy costs you are doing untold damage to the economy itself.

There are other options. Go for greater energy efficiency if you wish, that will reduce emissions without increasing energy cost. Get more production out of each gallon. Or support a shift from coal to natural gas. That shift does both—it reduces both energy costs AND emissions of CO2. Or for the third world solution, fog nets in Peru provide water for hillside dwellers without requiring energy to pump water up the hills. And as always, the mantra of reduce, reuse, and recycle combined with general energy conservation all can cut emissions without cutting CO2.

Because in all of this useless and futile fight against CO2, I can only implore everyone to follow the Hippocratic Oath, which says “First, Do No Harm“. And that means no carbon tax in any form, no “renewable mandate”, no “cap-and-trade”, because they all raise the cost of energy. A carbon tax, backed up by the anti-scientific political cover story for that tax called the “Social Cost of Carbon”, will do and in some parts of the world already is doing immense harm to both the economy and the poor. Carbon tax and the “Social Cost of Carbon” do uncalculated damage, they should be avoided completely.

My best to everyone,

w.

As Usual: if you comment, please QUOTE THE EXACT WORDS YOU ARE REFERRING TO, so that we can all understand your exact subject.

Previous Posts on the SCC:

The Bogus Cost Of Carbon

[See update at the end] From the New York Times a while back: In 2010, 12 government agencies working in conjunction with economists, lawyers and scientists, agreed to work out what they considered a coherent standard for establishing the social cost of carbon. The idea was that, in calculating the costs and benefits of pending…

Monetizing Apples And Oranges

Let me start by thanking Richard Tol, Marcel Crok, and everyone involved in the ongoing discussion at the post called “The Bogus Cost of Carbon”. In particular, Richard Tol has explained and defended his point of view, giving us an excellent example of science at work. In that post I discussed the “SCC”, the so-called “Social Cost of Carbon”. There…

Not taxing inputs makes sense for all the reasons you cite. It’s simply astounding how some people cannot grasp the idea. The progressive politicians in my state imposed an inventory tax on businesses a few years ago to provide more revenue for city and town governments. Of course, it harmed businesses by reducing their net income and distorting business practices such as limiting inventory in December so the January tax bite was smaller, for example. Of course, customers doing Christmas shopping didn’t like hearing that stock was sold out, but it could be ordered for pickup next month.

LikeLike

Thanks for that example, Gary. It’s not that hard to minimize the effect of taxation on the economy, but you do have to understand what you’re doing.

w.

LikeLike

Willis, excellent post.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Utopia – you are standing in it!.

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Tamar Conversations and commented:

Superb analysis of the insanity instilled in governments of all descriptions whose only objective is to destroy Western Civilisation.

LikeLike

Hi Willis,

My first post here. Tell me if you prefer me to disappear.

You are spot on about encouraging original wealth creation. Just last week one of my colleagues of old calculated that over 20 years the mineral exploration team we managed had, in today’s dollars, recorded sales from mines we found of some $62 billion with expectation of another $37 bn from continuing operations. That can be felt in Australia’s population of 24 million.

But there is downside. Imposters of imposts try for as much as they can get from anywhere -if not wealth generation somewhere else. In my case this more or less forced me to go from scientific to political mode to protect our wealth generation. The benefit to us all before that switch was orders greater than from after. This reinforces your message. The personal excitement from the latter phase was nil. Those who love challenge also have that reason to keep the hands of others off original inputs.

Geoff

LikeLike

What if the tax is levied over the output by calculating the amount of fossil energy that was used to create the final product? If a producer is unable to deliver a product (e.g. crops destroyed by external conditions) no tax will be due. I am just playing devil’s advocate. Of course is will only mean a delay in payment.

LikeLike

The same issue applies to tariffs or other restrictions on the import of basic commodities like sugar or steel.

Whenever we have punitive anti-dumping tariffs on steel for example, there is not doubt that the tariffs create jobs in the steel industry. However, there are many more manufacturers who are consumers of steel and who are rendered less competitive by the tariffs and they lose jobs,

LikeLike

Reblogged this on Climate Collections.

LikeLike

A taxpayer funded for the city of Boston just released its reccomendations to stop what they claim will be s 3′ rise in sea level. One of the ideas these bozos want is a tax on things such as driveways since the water runoff ends up in the ocean. someone needs to tell these clowns that is where the water came from.

LikeLike

An excellent article Willis, and I like your analogy of the seed corn. The trouble is the great majority of our political masters, and the people who voted them in, never made or grew or extracted anything, so they don’t understand anything about wealth creation. I’m a former teacher, so I consider I contributed to wealth creation in a small way by increasing skills, abilities, behaviours, attitudes, and thinking- but I’m also aware that the service I provided was paid for by the real wealth creators. Keep up the good work Willis!

Ken Stewart

LikeLike

Interesting post, as usual.

If I had a problem with it then it would be that you seem to assume that the folks proposing such taxes wish to raise revenue. What if their intention, all along, has been to reduce output?

As you suggested, taxing the seed corn only leads to less corn being planted. If your object is to have less corn planted then it’s an ideal tax.

Apply that to any other primary activity.

LikeLike

I lay awake last night thinking (dangerous I know) and I thought of a couple of questions for you.

What about industries/ occupations that facilitate wealth production and enhance productivity? Transport in particular consumes vast amounts of fuel here in Australia and if roads are cut by floods for a few days stores quickly empty. Or would you regard transport as an input to wealth creation? A fossil fuel tax on diesel would be a huge cost added on to producers and consumers.

The other cost of carbon apart from taxation is the diversion of resources to unproductive enterprises, away from medical, industrial, and agricultural research, health and education, and infrastructure like transport and dams.

LikeLike

I’m going for wealth creation. No point growing apples if you can’t get them to consumers. Transportation then becomes a necessity.

LikeLike

” A fossil fuel tax on diesel would be a huge cost added on to producers and consumers.”

But it’s a hidden tax. If, as a government, I tell you that income tax will be increased by X next year then you ain’t going to vote for me come the next election. Put the tax further upstream and you get the same revenue stream only a hidden one.

LikeLike

Pingback: Economic Cost Of The Social Cost Of Carbon | US Issues