When there’s no fog on the coast, from my kitchen window I can see a tiny triangular patch of ocean in the distance. It’s my door to adventure, emblematic of my lifelong affection for, my addiction to, the everlasting sea.

I was raised on tales of my great-grandfather, who grew up traveling the world on his uncle’s armed sailing trading frigate before the US Civil War. After that long-ago war, he was a steam tugboat captain on and around the lower Mississippi. He was one of my heroes. I learned to sail when I was maybe ten years old, thanks to my dad. My father couldn’t sail a lick but thought his sons should know how. We spent every summer at his house on San Francisco Bay. When I was 12 I was single-handing a ten-foot (3m) sailboat around San Francisco Bay, totally unaware of how foolishly dangerous that was and how lucky I was to not become a statistic. The Bay is a hungry body of water … it eats a couple of people every year.

As a teenager, I sailed and body-surfed and snorkeled in the ocean every summer whenever I could. And after I left the cattle ranch where I grew up, I moved to the coast and have lived near the coast ever since.

Now, being addicted to the ocean, to sailing and surfing and diving has an ugly symptom … chronic lack of funds. I couldn’t just sail and swim and surf. I had to figure out some way to make money on the ocean so I could maintain my soggy lifestyle.

After not making my fortune mining gold in 1969, I went back to Santa Cruz, California. Santa Cruz is a fishing town. It’s on Monterey Bay, home of Steinbeck’s famous “Cannery Row”. I still held on to my dream of commercial fishing. If anything it had grown stronger from being frustrated in Alaska, where I had gone to get a fishing job, but I hadn’t gone fishing even once. I walked the Santa Cruz docks day after day, just like I’d walked the docks in Alaska, and I asked the fishermen about work. And guess what? Same old story in both places.

(1) You can only get a job if you have experience fishing.

(2) You can only get experience fishing if you can get a job.

Catch-22. I swore that if I ever got to be a fisherman, I’d take folks out and teach them to fish if they wanted to learn. And I’ve done that at every opportunity. But that didn’t get me a job back then.

Finally, a friend of mine came by one morning. He was working as a fisherman on a small boat owned by a Sicilian. Most of the fishermen in the Monterrey Bay were Italian or Sicilian at that time. My friend said he was going to go to Canada to avoid the draft. I wished him well. He said he was going to leave that very day. He was supposed to be going out fishing at dark (it was a night fishery). He said I should just show up with the other crewman, who was also a friend of mine.

So I did. The owner, Sam Mazzerino, looked me over when I turned up. He was clearly unimpressed … and in hindsight, rightly so. But there wasn’t much he could say—he needed to go out fishing right then, and he needed two guys for a crew. So reluctant and grumbling, he took me on.

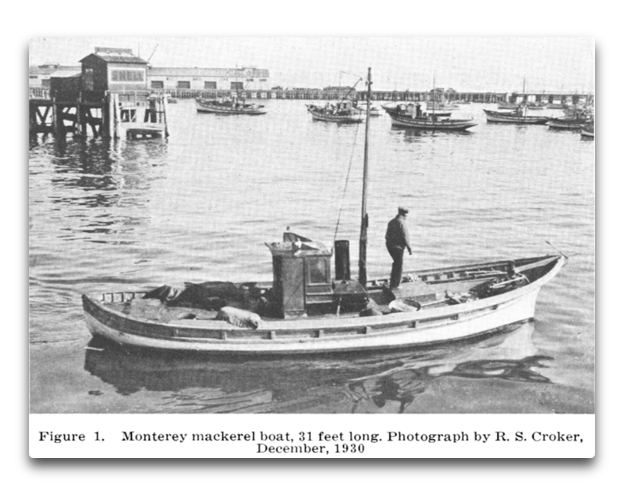

Sam’s boat was a small powerboat, about 23 feet (7 m) long, with beautiful lines. It looked a whole lot like the boat below.

I learned in later years that the style was native to the area, called a “Monterey style” fishing boat. It was descended from the Italian fishing sailboats called “silenas”.

Below is an aerial photo of Santa Cruz Harbor, including the pier. Santa Cruz is a good place to fish because it’s pretty well protected. The harbor where Sam kept the boat is at the upper right. You can see the Santa Cruz Marina, rows of boats. Wind is usually from the northwest, top left in the picture, leaving the seas fairly calm in the area shown above … unless it turns to blow from the southwest, when it can get what fishermen call “nautical out there” ….

We got to the harbor right at dusk, with few people around. We loaded large wooden boxes with rope handles, “fish boxes”. Sam fired up the boat, I undid the bow (front) lines that tied the boat to the marina pier. The other crewman untied the stern (back) lines. We got on board and motored out of the harbor into the night.

There was not a happier man in miles …

I cannot say that my first night’s fishing matched my dreams of fishing for a living. I cannot say that, because it exceeded them entirely, blew them into dust. The night was clear, with a half-moon. The sea was enchanting.

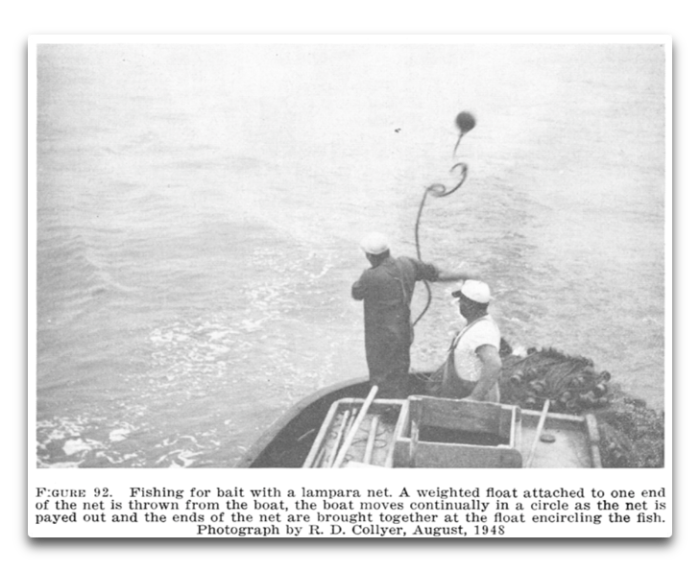

Sam fished using a kind of net called a “lampara” net. Lampara means “lightning”. Sam said it was a lampara net because you could set it so fast. The fishing was done entirely at night. First, we’d cruise around looking for the fish. At night off of Santa Cruz, the sea is full of phosphorescent creatures. Wherever anything moves, it leaves a glowing trail behind it. Here’s the blue glow in waves along the coast …

We were targeting the small fish called “pompano” shown below, although we sold whatever we caught. Pompano school up at a depth of about ten fathoms (eighteen metres). Schools of pompano can be distinguished from other fish by how the school moves when you stomp on the deck. At least they can be distinguished if you’re Sam Mazzerino, Sicilian fisherman extraordinaire. I eventually got passable at the skill. But that first night, all I saw were dreamlike slow-fading luminous blue-green flashes of light way down in the depths. “At-sa no pompano,” Sam would say if they weren’t what he wanted, “at-sa mackerel” or any one of a half-dozen other species.

I watched, entranced.

When he found a school of pompano, Sam would see which way they were moving. Then he’d set the net in a semi-circle around the front end of the school. That way the fish were swimming into the net. A lampara net doesn’t close up with a purse-string like a seine net. It’s always open on one side, the side under the boat. So you throw a waterproof 12 volt light overboard connected by say thirty feet (nine metres) of electrical cable. You flash the light on and off to scare the fish back into the net.

Because one side of the lampara net remains open, you have to work fast. You bring the nets in with the aid of a winch that helps you pull the net, but at the end it’s all by hand, standing on a pitching deck and heaving up the net. I never saw Sam fall down from the waves. We swore he had magnets in his feet. True, he was built to a Sicilian blueprint, short and wide with a low center of gravity, but he was still amazing. Especially at first, I was tossed around when I walked, staggering like a drunk. He just went where he wanted. He had spent his entire life at sea.

That first night, we were fishing right off of Santa Cruz. The Santa Cruz waterfront has a long dock connected to a boardwalk along the coast with carnival games and rides.

After dark, the Santa Cruz waterfront is a brilliant sea of light, with the Boardwalk rides and the Giant Dipper roller-coaster all lit up. People were having a good time there, and I gazed in awe at the spectacle while the net ran out over the back of the boat. We worked set after set, out there unseen by the folks strolling along the boardwalk. It’s a very curious feeling, working hard out in the dark while people are playing nearby.

And then, as we were making a set, Santa Cruz lost power. All the lights went out, nothing but blackness and a few emergency lights. Now the whole scene was lit only by the deck lights and the moon. It was stunning, like we’d fallen into some strange dark ocean far from land.

To my great surprise, I heard a breath from the ocean and looked down. A big sea lion had surfaced, drawn by the net and the boat’s deck lights. He dived and streaked away. When he left, without the interference of lights from the boardwalk I could see his glowing trail like some underwater green comet, growing smaller and smaller in the distance, and finally fading and mixing with the silvery moon-glow on the water … and in that moment, I knew that I had finally realized a livelong dream.

I had grown up on the ranch and dreamed of the sea. I had gone to Alaska to make my fortune fishing and ended up with a face full of rotten crab. I had tramped the docks in Santa Cruz and Moss Landing getting rebuffed time after time.

But it was worth the wait. Even if I had only ever fished that one enchanted night, it was worth the wait. I had realized my dream, and it was better than I could have dreamed.

Sam was great. Me and my buddy that fished for him had long hair. He didn’t care, the question was, could we fish? We could. We showed up every night. One night I was sick as a dog, so was my buddy. We went to see Sam. When we said we were too sick to fish, the look on his face said it all. It said “Sam Mazzerino has been sick, but never in his life has he been too sick to fish.” We couldn’t take it. We couldn’t meet his eyes … and of course, we went fishing with him just like always. A matter of honor among fishermen, and a wonderful lesson for a young man such as myself.

Sam had an uncanny instinct for the fish. When we were headed out of the harbour we’d say “Sam, where are the Pompano tonight.”

“Jesakreisalminey, how’m I gotta know? You thinka the fishies send me a telegraph?” He’d laugh, then he’d sniff the air and look at the night and usually go right where the fish were, sometimes off the Santa Cruz Pier, sometimes in down the coast.

One day my buddy and I went to the Western Union office and sent Sam a telegram. It said “SAM WE ARE GOING TO BE IN CAPITOLA TONIGHT SIGNED THE POMPANO” When we met up at the boat at dusk that night as always, he said “I getta telegram today. I think maybe we fish in Capitola.” That was it. Not a smile. We left the harbor and turned the other way. We set the nets off the Santa Cruz Pier, and caught a good load of pompano. He said “I think the fishies change-a the mind, eh?” and laughed a warm laugh.

When the fish were caught they were brought up and dumped on deck. The variety of fish in the Monterrey Bay is large, it is a very prolific ecosystem. We caught blue shark and thresher shark. We threw the blues back and ate the thresher sharks. That was before I did much diving in the ocean. Later, when I was spending lots of time either surfing or diving down below the surface, I made a pact with what us surfers call “the man in the gray suit”. The pact was, I’d quit eating shark, and I sure hoped that the men in the gray suits would forgive my past youthful transgressions and not eat me either. But that was still years in the future. Then, we ate the threshers, they were delicious. Occasionally we’d catch a sturgeon, three or four feet (one metre) long. They looked like something from a million years ago, which I guess they are, all hooks down the back and the side. We threw them back overboard, they were rare and it was illegal to take them in the ocean.

Sorting the fish was great sport. We sorted pompano by size. If we only had a few fish, Sam would have us sort them into Big and Small. When there were more fish, at some point he’d say “Make-a the medium pompano”. We’d kick another box in line and sort that way. Sam couldn’t come past without taking a fish from one box, weighing it in his hand, and moving it to another box. As the fish increased, we had Extra Large and Extra Small as well. And one memorable night, when we filled up the boat, we had a category ambiguously called “Extra Medium”. We laughed at the idea of something that was really, really medium. Super average.

Most of the fish Sam would put into his refrigerated truck. Two days a week we had off, and he’d drive the truck around the Salinas Valley. He had a route, selling the fish to housewives. The rest of the fish we trucked up to Chinatown in San Franciso. There, we would sell the fish to the Chinese fish merchants.

Doing business with Chinese folks sometimes hasn’t gone in the direction I’ve expected it to take. There’s often some curious twist in the story. We’d put the fish in the back of Sam’s truck and drive up to Chinatown in San Francisco. Sam knew all the merchants. We went to the first one. “How much-a you pay,” Sam said. He actually talked like that, like some Italian in a cartoon. “Fi’ cent” came the answer. “Five-a cent!” Sam would shout, “Last-a time you give ten”. I eyed the young Chinese guys cleaning and gutting fish while Sam talked to the owner. They all used razor-sharp cleavers. A cut, a slice, a few well-aimed chops and it was done.

One day, after weeks and weeks of this same stuff, Sam couldn’t take it. He stomped out, irate at some eight cent offer for Extra Medium pompano or something. We went to the next guy. “Seven cent,” he said. The next guy said six. We went back to the first guy. Only this time around, he only offered “fi’ cent”. Sam said “You said eight cent!”. The Chinese guy shrugged his shoulders. “OK, boys”, Sam said, and we left the fish shop.

When we got out on the street. Sam swore in Sicilian, unusual for him. I could see the steam coming out of his ears. His usual big swear was “Jesakreisalmianey”, which was so slurred it had taken me a week to translate it to “Jesus Christ Almighty”. He pulled over and parked in the street. He opened the back. He said, “Sell-a quick, boys, we no gotta much time. ” He sang out in inimitable Sam fashion “Cheap-a pompano! Caught-a last night! Fresh-a Pompano!” Immediately we were swamped in a tide of Chinese housewives … and I can tell you, a rugby scrum of Chinese housewives is a shopping team which gives no quarter. The crowd kept growing and pressing in on us, people all talking Chinese at a rate of knots. We charged a dollar a bag, we charged a dollar for three fish and a dollar for five fish. We gave no ground, we offered no change. At some point, Sam tapped my arm and pointed. It took me a minute to extract my mind from the pull of the retail maelstrom. I took in the scene one detail at a time.

Three Chinese guys were leaning against a storefront.

The three Chinese guys leaning against a storefront all had fish buyer aprons on.

The three Chinese guys leaning against a storefront with fish buyer aprons on all had a razor-sharp cleaver in one hand. I noticed that one was left-handed.

The three Chinese guys leaning against a storefront with fish buyer aprons on and a razor-sharp cleaver in one hand, one of them left-handed, were all rhythmically slapping their cleavers against the palm of their other hand, in time with each other.

And they were all staring at us.

I looked at them. I looked at Sam. He looked as inscrutable as they did. I looked back at the gentlemen with the cleavers. One of then silently used his cleaver to point down the street. We nodded. We shut the back door, jumped in the truck, and drove out of Chinatown. Sam sold those fish on his Salinas Valley truck route.

Sometimes when the fish were all sold, we’d sit and drink grappa. It tasted horrible and kicked like a badly timed Harley-Davidson motorcycle when you try to start it … that grappa would throw your hat three feet in the air, with your head still in it. And if we could get him just drunk enough, Sam would tell stories of his childhood. His father was a fisherman. They fished under sail, no engine. They used a kind of net called a “pair trawl”. The two ends of the net were each attached to a different sailboat because a single sailboat couldn’t pull that big a net. There were four or five guys on each boat. They had a whole set of hand signals between the captains to control the movement of the vessels. They fished out of Sicily, where the waters had been fished for centuries and catches were always bad.

They were desperately poor and at the bottom of the social food chain. Because he’d grown up in Sicily, America to Sam was heaven. He had his own boat. He had his refrigerated truck. He was respected by his neighbors. He’d come to America and made good, a successful immigrant employing two gringos.

Commercial fishing is generally done on shares. As a crewman, you get a share of the profits. Nobody gets a wage. Everyone fished on shares in those days. On Sam’s boat, the “Vita Marie”, there were four and a half shares. Every man including Sam got one share for their work. Fair enough, we all worked the same. The boat (in the form of Sam) got a share and a half. That was fair, it was Sam’s boat and he met all expenses. End of the week, we’d total up and Sam would pay us. We’d check the weight slips, check the figures, make sure our shares were right, shake hands, and go back to fishing.

Sam told us how sharing out the profits worked back in the old days. I think I can say without fear of contradiction that Sicilians are not generally known for trusting their neighbors when it comes to money … in fact, rumors say the opposite. In addition, most of the fishermen were illiterate and somewhat innumerate as well. How could they be sure that the Captain wasn’t cheating them?

So at the end of the trip, they’d offload the catch. Everyone would stand around and watch the fish buyers, because all commercial fishermen know that every fish buyer on the planet is an unmitigated crook whose scales weigh light… and the fisherman are sometimes right. So the crew would stand around, and watch the scales, and watch the Captain get paid. In small bills.

Then they’d retire to the boat to divide it up. Everyone sat around the table. The Captain had the money, in one stromboli notes or whatever the Sicilian currency is. He’d go around the table. “One stromboli for you, one for you, one for you” and on around until he got to one for himself, then “and nine stromboli for the ship” or whatever the ship’s share was. Big ship, big share; small ship, etc. The Captain would go around and around. At some point, he’d see that the last fifteen stromboli wouldn’t make it all the way around the table plus the ship’s share.

And with that remainder, the amount of money that couldn’t be split equally, they sent out for however much grappa the last few stromboli would buy, and sat around the table and drank until it was gone … and then they’d go back to fishing. That way everyone knew that they were getting paid the same, and nobody was getting any extra money out of the deal.

I don’t want to romanticize Sam. He knew two kinds of northwest winds, the “good north-a west”, and the “poison north-a west”. But he didn’t try to outguess the weather. One night he said “Big-a storm come tomorrow”. I asked “How’d you know, Sam”, expecting ancient Sicilian weather knowledge. “Channel Seven-a News,” he beamed, “pretty girl too”. And electricity was a mystery to him. He knew that positive had to go to positive and vice versa, but his electrical knowledge stopped there. He had grown up where boats and houses both used kerosene lamps. But he was a consummate seaman, a man who was never surprised by wind or wave.

Fishing is one of the most dangerous occupations in the US. If you want to design a truly hazardous workplace, you couldn’t beat the fishing boat. The workplace regulations on a factory floor require things like nonskid matting, and no unusual protrusions to trip over. The deck of a fishing boat is covered with fish scales and slime, and it is studded with cleats and eyebolts and hatch covers. On land you have guards for anything dangerous. We used winches to help pull the nets. No guards on anything. But not only that, the whole workplace is constantly shifting, moving and tilting. Occasionally sharks with scary teeth are flopping on deck. Heavy weights are swinging overhead. Same in the engine room, exposed belts, whirling metal. Poor lighting. No safety guards.

And around that, and always on our minds, the ultimate friend and enemy, the sea itself. Every fisherman loves and fears the ocean. I love the egalitarian nature of the sea. If you make a mistake and “try to walk on water” as fishermen say, you’ll get wet whether you are a beggar or a banker, a pauper or a Pope. The ocean cares nothing about man and his titles, costumes, and grades. Walk on water and you’ll get wet. Make a mistake, and you may die. Doesn’t matter who you are. Simple as that. Scary as that. I like it that way.

One night I made a mistake. It was the usual three-man crew—Sam, my friend, and I. Pulling the net requires one man on each winch to pull in the two wings of the net. The odd guy would pick sticks and branches and such out of the net before they got to the winch. I was picking junk out of the net when my hand got caught in the net. The winch started winding my arm around the winch drum. I couldn’t get loose, and from there I couldn’t reach the winch shut-off. By the time I had screamed, and my buddy had dived headfirst halfway across the deck and hit the winch shutoff, I was a couple seconds from losing my arm. It was jammed and wrapped backwards halfway around the winch when it stopped. The winch would have ripped it off.

When Sam and my friend had wound the winch backwards by hand until my arm came free, and once my heart-rate dropped down out of the triple digits … we went back to fishing. It’s what fishermen do. The danger is always present. You live with it.

When we were actually setting the net, death was always one misstep away. The net sits in a pile on the deck, hopefully stacked so it will run free and clear out over the back. We’d set the net with the boat moving at high speed to encircle the fish quickly. When the skipper yelled to set the net, we’d put the lighted float in the sea over the side of the boat. The lighted float was tied to a rope attached to the net. That way the skipper could circle round and end up back at the start of the net.

Once the lighted float was in the sea and we’d pulled away, we’d hand toss some of the net into the water. Immediately the net started streaming out over the stern (back end) of the boat as the boat moved forward. Net on the deck was constantly pulled out by the net already in the water. We’d jump back and watch the net. The “cork line”, the rope running along the top of the net with the big corks threaded on it at intervals, was stacked on one side of the boat. The “lead line”, a rope with a lead core that runs along the bottom edge of the net, was stacked on the other side. The lead line slithered over the edge like a snake. The corks clumped and banged on the deck and got occasionally stuck on another cork or something on the deck.

When everything ran smoothly, we just stood well out of the way and didn’t touch the net at all as it was shooting out over the stern. The danger, of course, was that if the net caught on you, if it caught on your boots or your watch or wrapped around your leg, it could yank you over instantly. The point of danger was when the corks got twisted or caught on the rail. We’d have to go in next to the net stack to free it. As soon as a cork got stuck, the line started to tighten, pulled by the boat’s unceasing motion but held by the net in the water. By the time one of us could yank the cork free, the strain could be huge. When the jammed cork was released the net would be pulled out at high speed over the side, whipping and bouncing as it went. When the jam came loose we scrambled for safety.

Or my personal favorite fear. In this one, the cork line (as often happens) takes a loop around some corks way down in the net stack. Someone jumps in to pull it loose. But if he can’t get it loose, the boat keeps moving and the loop tightens. Only one possible outcome, I’ve seen it many times. Because the line is wrapped around a cork deep in the stack, a big chunk of the whole net stack goes over at once. It all dumps over the stern in a huge welter of hundreds of feet of corks and lead-line and netting … and perhaps with an unlucky crewman in the middle, moved too slow, got caught in the titanic net-slide, dragged overboard wrapped up in layer after layer of netting that the lead-line is pulling inexorably down to the ocean bottom …

And then, as we used to say on the boat, the Devil better help you, because even God couldn’t find you under all that net.

I loved it. The proximity of danger is part of the joy. At another time in my life, we called it “feeding the rat,” as in “I’m bored. I gotta go do something to feed the rat.” The joke was that the rat lives on just one thing – adrenaline.

Surfing, commercial fishing, night scuba diving, taking a kayak through crazy whitewater, ultralight airplanes, that kind of thing is feeding the rat for me. I never got to go to Disneyland as a kid. Instead, my life has been a real-world Disneyland E-Ticket ride all the way, and I’ve spent much of it on, over, and under the ocean.

And the truth is, I can’t help it. I’m an addict, and when that ocean bug bites you … well, you just gotta live with the sting. Writing this, I am reminded of the words of the poet laureate of the California coast, Robinson Jeffers:

A sudden fog-drift muffled the ocean,

A throbbing of engines moved in it,

At length, a stone’s throw out, between the rocks and the vapor,

One by one moved shadows

Out of the mystery, shadows, fishing-boats, trailing each other

Following the cliff for guidance,

Holding a difficult path between the peril of the sea-fog

And the foam on the shore granite.

…

The flight of the planets is nothing nobler; all the arts lose virtue

Against the essential reality

Of creatures going about their business among the equally

Earnest elements of nature.

from Robinson Jeffers, Boats In A Fog

My very best wishes to all of those who dare to venture “between the peril of the sea-fog and the foam on the shore granite”. It is a wonderful albeit deadly world out there.

So take care to stay safe out on the briny water, dear friends, and as always … keep feeding the rat …

w.

To quote the exact words about what I like here, I would have to cut and paste the whole lot! Thanks for sharing this with us …

LikeLike

Thanks W…really enjoyed reading about your ocean ffishiing asventures. My Dad and his brothers…Jim and George had a fishing boat and business out of Newport Beach and Costa Mesa where before I was born umtil WW2. My Dad joined the Navy…became a Navy Chief. My Uncle Jim joined the Marines and became a Hellcat fighter pilot…sadly getting shot down and killed on a straffing mission in the South Pacific. My Uncle George hsd a physical deferment. They were all Cornell Grads like my Grandpa Knight. They had an adventerous life growing up hunting and daily fishing on Lake Chautauqua not far from Cornell.

Thats why my Dad msde sure we grew up fishing and hunting in Redding which like yourself I’m forever grateful for. :-))

LikeLike

Thanks, Jim, always good to hear from you, and welcome to the blog.

w.

LikeLike

Dammit, Willis, you add to my smile.

It seems we have tasted many similar flavours of life. Feasted, too. Right now, I am focused on caring – itself a flavour to be savoured by those who really love. My bride of fifty years had a total knee replacement twelve days ago, so my focus temporarily is indoors.

It’s early spring here in NZ. Our garden is untended and growing free – gathering food is in it is a safari into jungle undergrowth. The mullet and snapper beginning to return to the firth are safe from my predation for a while.

Bride is recovering apace, so soon I will be back out there clearing and planting. She won’t be far behind. Normally we share all domestic and foraging tasks, and she will be frustrated as long as I get to do all the outside stuff. Especially the fishing!

Keep the posts coming, man – here and over on WUWT

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for the kind words, John, and best wishes to the bride …

w.

LikeLike

Thanks Willis, made me think of this:-

LikeLike

Fabulous storytelling, Willis, I loved every word of it!

LikeLike

Your fish tales are my favorites, Willis, and my favorite of your fish tales is whichever one I’ve just finished reading. 👍

I’m in the mid-west and I fish just about every day that the water is not completely frozen over. My vacations consist of going to the ocean so I can fish saltwater. I really enjoy your nautical adventures, but when I’m reading them, I’m always wondering about what fish might be below while you’re telling us about the goings on above the water line.

You wrote how Sam always knew where the fish were. Maybe it was because he was able to ‘think like a fish.’ That’s a big part of the enjoyment I get from fishing. Oh sure, the catching, the pull on the end of the line, the sluggers, the jumpers, the fast runners, and the beauty of the various fish are part of my addiction, but I just like to let my mind get really primal and try to ‘think like a fish.’ Everything else, including time, just goes away,

Anyhow, that’s my guess as to what was behind Sam’s uncanny ability to find fish. That, or else he really was getting telegrams from the fish, and he knew your telegram was a fake because it was signed wrong. 😜

.

.

Oh, I got a big kick out of the fish sorting and the extra medium category. I classify fish as I catch them: snack size, small regular, regular regular, large regular, small jumbo, jumbo. No kidding. I’m going to have to add the category of ‘Jesakreisalmianey’ when jumbo just won’t do. Thanks, Willis. Thanks, Sam.

LikeLike

Thanks, H.R., lovely comment.

w.

LikeLike

A guy fishing out of Annan on the Solway Firth wasn’t quite as lucky as you, Willis, he was out single handed, got his arm caught just as you did and in fact lost his arm.

Went back fishing as soon as he recovered, though. Like all of us he needed to feed the rat.

LikeLike

Thanks, Seadog, always good to hear your voice. Yes, I could easily have lost my arm … I was very lucky.

w.

LikeLike

Willis, great story as always. I was curious about the Chinese buyers. Was that episode the last time you dealt with them, or on the next trip was it business as usual?

LikeLike

The next trip was business as usual. They were realists, and we were the only people fishing for pompano, which is a huge favorite in Chinatown.

Welcome to the blog,

w.

LikeLike

“The night was clear, with a half moon. The sea was enchanting.”

Not addicted to the ocean, enchanted by it, I think, but you would know better. Addicted to the rat, that I would believe. Moonlight on the waves alone on the ocean and phosphorescent creatures at sea have to be seen to be believed. Nothing is so enchanting.

Great story telling, but I wonder why you feel writing your stories is different from recording your music? (even if live is better)

LikeLike

Thanks, YMMV. Not sure why writing the stories is different from recording the music …

w.

LikeLike

Excellent read, Willis! Takes me back to shrimping and fishing in the Gulf of Mexico as a teenager in the ’70s on my uncles’ boats out of Bay St Louis, Dulac and Morgan City. Open water, ain’t nothing like it!

LikeLike

Pingback: Terminator Winds | Skating Under The Ice

Pingback: Dungeness Crabs Redux – Weather Brat Weather around the world plus

Pingback: Dungeness Crabs Redux | Watts Up With That? – Daily News

Pingback: Fish Food Dungeness Crabs Redux – happyaquariums.com

Pingback: The 11th 10th First Local weather Exchange Refugees – Daily News

Pingback: Bereits zum zehnten oder elften Mal die „Ersten Klima-Flüchtlinge“ – EIKE – Europäisches Institut für Klima & Energie

Pingback: Bereits zum zehnten oder elften Mal die „Ersten Klima-Flüchtlinge“ - Leserbriefe

Pingback: Bereits zum zehnten oder elften Mal die „Ersten Klima-Flüchtlinge“ - BAYERN online

Pingback: Climate Change Refugees | US Issues

Pingback: Ozeanische Hybris | EIKE - Europäisches Institut für Klima & Energie

Pingback: Ozeanische Hybris – Aktuelle Nachrichten

Pingback: Fishing for Citations - Western Highlights

Pingback: Fishing for Citations – Watts Up With That? – ChicHue.com

Pingback: Dungeness Crabs Redux - Science Radars | Where the world discusses science.

Pingback: The Twelfth First Climate Refugees - Climate- Science.press

Pingback: It’s Not About Me – Watts Up With That?

Pingback: Salty News From An Old Salt • Watts Up With That? - Lead Right News

Pingback: Salty News From An Old Salt • Watts Up With That? – The Insight Post

Pingback: Salty News From An Old Salt - Climate- Science.press