I used to be a strong proponent of free trade, until I read “How Rich Countries Got Rich … And Why Poor Countries Stay Poor” by Erik Reinert. His exposition is a tour-de-force, covering the actual history of trade, tariffs, and how England, France, and Germany used them to become wealthy.

$11.99 on Kindle, used copies from $2.21. Someone asked if I could give a summary. Reinert points out that opposition to free trade is not a new idea. He provides, in an appendix, a most interesting document from the year 1684 by an economist named Philipp von Hörnigk, with the lovely title

Nine Points on How to Emulate the Rich Countries

How do you get rich? You do what the rich countries do. What I’m going to do is put Hörnigk’s text inset and bold, with my comments interspersed. Here’s his first point.

First, to inspect the country’s soil with the greatest care, and not to leave the agricultural possibilities of a single corner or clod of earth unconsidered. Every useful form of plant under the sun should be experimented with, to see whether it is adapted to the country, for the distance or nearness of the sun is not all that counts. Above all, no trouble or expense should be spared to discover gold and silver.

It is interesting that although Hörnigk’s main thrust involves manufacturing, because it has a greater return, his first point is to look at what can be grown in the country. Plus gold and silver, of course, as that was real money in 1684.

Second, all commodities found in a country, which cannot be used in their natural state, should be worked up within the country; since the payment for manufacturing generally exceeds the value of the raw material by two, three, ten, twenty, and even a hundred-fold, and the neglect of this is an abomination to prudent managers.

Agriculture and extraction (mining, logging, fishing) both suffer from diminishing returns. You can increase the yield of your gardens with fertilizer. But each additional pound of fertilizer brings smaller and smaller returns.

Manufacturing goes the other way. Mechanization and economies of scale allow greater returns than either agriculture or mining.

And in particular, manufacturing using your own products from agriculture or extraction is crucial. Manufacturing can increase the value of your raw agricultural products by ten-fold or more. This is why manufacturing is more important than either extraction or agriculture-the value multiplier of manufacturing is very large. You want to add the value in your own country, and to keep the jobs in your own country.

Third, for carrying out the above two rules, there will be need of people, both for producing and cultivating the raw materials and for working them up. Therefore, attention should be given to the population, that it may be as large as the country can support, this being a well-ordered state’s most important concern, but, unfortunately, one that is often neglected. And the people should be turned by all possible means from idleness to remunerative professions; instructed and encouraged in all kinds of inventions, arts and trades; and, if necessary, instructors should be brought in from foreign countries for this.

Next, he says, focus on the people—education, and encouragement of entrepreneurship, training, good stuff.

Fourth, gold and silver once in the country, whether from its own mines or obtained by industry from foreign countries, are under no circumstances to be taken out for any purpose, so far as possible, or be allowed to be buried in chests or coffers, but must always remain in circulation; nor should much be permitted in uses where they are at once destroyed and cannot be utilized again. For under these conditions, it will be impossible for a country that has once acquired a considerable supply of cash, especially one that possesses gold and silver mines, ever to sink into poverty; indeed, it is impossible that it should not continually increase in wealth and property. Therefore,

Here Hörnigk is cautioning against the very situation we have today, a huge trade deficit with the rest of the world. Bad idea.

Fifth, the inhabitants of the country should make every effort to get along with their domestic products, to confine their luxury to these alone, and to do without foreign products as far as possible (except where great need leaves no alternative, or if not need, widespread, unavoidable abuse, of which the Indian spices are an example). And so on,

This fifth point is where the question of free trade starts to be discussed. Hörnigk is very emphatic that trading your wealth for foreign products when domestic products are available is a foolish move.

Sixth, in case the said purchases were indispensable because of necessity or irremediable abuse, they should be obtained from these foreigners at first hand, so far as possible, and not for gold or silver, but in exchange for other domestic wares.

When he says “at first hand”, he means without middlemen, directly from the producers. He’s also clear that what is important is the net trade deficit, and that if you can sell an equal value of goods overseas, that is preferable to just spending your wealth on imports.

Seventh, such foreign commodities should in this case be imported in unfinished form, and worked up within the country, thus earning the wages of manufacturing there.

Here he’s making the point again about manufacturing. If you have to import something, import raw materials and make the finished goods yourself.

Eighth, opportunities should be sought night and day for selling the country’s superfluous goods to these foreigners in manufactured form, so far as this is necessary, and for gold and silver; and to this end, consumption, so to speak, must be sought in the farthest ends of the earth, and developed in every possible way.

Here is “globalization” in a different form. Hörnigk is looking at global markets for the country’s products.

Ninth, except for important considerations, no importation should be allowed under any circumstances of commodities of which there is a sufficient supply of suitable quality at home; and in this matter neither sympathy nor compassion should be shown foreigners, be they friends, kinfolk, allies or enemies. For all friendship ceases, when it involves my own weakness and ruin.

And this holds good, even if the domestic commodities are of poorer quality, or even higher priced.

For it would be better to pay for an article two dollars which remain in the country than only one which goes out, however strange this may seem to the uninformed.

This is a critical point, because it speaks directly to the main argument in favor of free-trade. This argument is that free trade leads to lower prices for consumers. They are correct. It does.

But as Hörnigk points out, it’s better for the country to pay two dollars for a local product rather than one dollar for the Chinese version … and that is why Hörnigk says that “no importation” should be allowed of products if there is sufficient supply and quantity at home.

The net effect of free trade on the US has been two-fold. The first is the loss of thousands and thousands of manufacturing jobs. Manufacturing, as Hörnigk points out over and over, is critical to the ability of the country to produce and hold on to wealth.

The second is the loss of our wealth through a large and ongoing trade deficit.

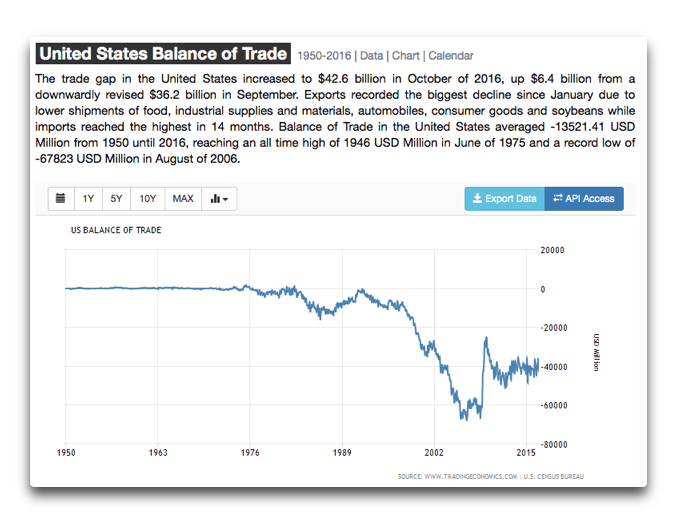

People look at me strangely when I say that when I was a kid in the fifties, the US ran fine with almost no overseas trade at all, and that we had no trade deficit with the world until the 1970’s. But it’s true. The trade deficit in 1992 when NAFTA was signed was around zero … and from there, we started hemorrhaging our wealth overseas.

This is why Hörnigk says:

For it would be better to pay for an article two dollars which remain in the country than only one which goes out, however strange this may seem to the uninformed.

In my last post on the subject entitled Why Free Trade Isn’t I talked about the Honiara Nail Mill. I described the loss of the mill to free trade. It is true that nails from the funky little local mill were more expensive than nails from the shiny new mill in Singapore, and under free trade it could not compete.

But the cost of free trade to the Solomons is immense. The cost is the loss of a manufacturing sector in the Solomon Islands, and that sentences the islands to an eternity of being nothing but a poor country that is just a producer of raw materials and nothing else.

Anyhow, that’s the basic story. However, I cannot truly do Reinert justice, and I encourage you to get the book from your local library if you cannot afford it.

Best wishes to everyone, free-traders and protectionists alike,

w.

My Usual: If you comment on someone’s work, please QUOTE THE EXACT WORDS THAT YOU ARE DISCUSSING, so we can all understand just what you are talking about.

Further Reading: There’s a fascinating review of “How the Rich Got Rich” at the same Amazon site. It’s the first review, just under top section. It’s actually a concordance and obviously a work of love. It lays out the basic ideas of the book, with page numbers … amazing.

Venezuela and Saudi Arabia demonstrate what “domestic product” without work force productivity brings.

As for gold, bury it, hide it. Big Brother wants it. Thus it’s best in small (1oz or less) quants in your stash. 10 oz bars suck (as I now realize).

Merry Christmas Willis to you and your former finacee.

LikeLike

Thanks for the post, Willis. Hornigk reminds me if the Wotld Systems Theory from Anthropology…https://en.m.wikipedia.org/wiki/World-systems_theory

LikeLike

I would point out that the manufacturing sector job loss is not matched by lower manufacturing output. There are a number of reason’s offered for this, but it is still the largest sector in the economy. It’s output has doubled in the last three decades, and it has maintained its fraction of the nation’s wealth production for the last 40 years. Today, U.S. factories produce twice as much stuff as they did in 1984, but with one-third fewer workers. Efficiencies, automation, and outsourcing of facility services [janitorial etc..] have all led to declines in the number of people employed in manufacturing, just as had occurred in agriculture [we went from a country 97% employed in AG to 3%, all the while increasing AG output]. The only point relevant here would be that the metric for the health of the sector should NOT be employment, or by that measure our AG sector would be declared a complete and utter failure. In fact, maintaining output while reducing inputs [labor, material, overhead burden] is more often considered a measure of economic health.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Randy B December 20, 2016 at 10:25 pm

Huh? Manufacturing as a fraction of GDP has been steadily dropping for at three decades and more.

w.

LikeLike

I have not seen the stat your chart refers to. I can’t seem to post a picture of real output, but I was referring the FRED Economic Data; Mfg Output as referenced here: https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/OUTMS

I’m uncertain how to reconcile the difference as I’d never run across the value added metric before.

LikeLike

Willis, Randy is referencing an index of real manufacturing output (most likely measured in constant dollars) and you’re talking manufacturing value added as a percent of GDP. If the services sector of the economy is growing faster than the manufacturing sector, manufacturing will drop as a percentage of the total even though manufacturing is growing in real terms. As for Randy’s statement that manufacturing “has maintained its fraction of the nation’s wealth production” I am not sure exactly what statistic he is referencing, but it may not be the same thing as manufacturing value added / GDP.

LikeLike

I should have included source reference; https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/OUTMS

LikeLike

I had bought into Ricardo’s and Friedman’s ideas that free trade and unrestrained competition ultimately would give the best results for the most people. In the long run, and ignoring country-specific consequences, those ideas may be true. However, your summary of Hornigk and the Amazon summaries of Reinert suggest I need to read this, and similar expositions, and possibly reconsider my views.

LikeLike

Krugman got awarded an “Economic Nobel” for his work on Free Trade, publishing interpretations of Ricardo’s work.

He puts forward arguments in his 1996 essay championing Free Trade “RICARDO’S DIFFICULT IDEA”. He states it is a concept that seems simple and compelling to those who understand it, but then writes many pages explaining why nobody seems to understand it, and why many oppose the idea. His argument:

1. Free trade has an iconic status, so some simply oppose it to appear “daring and unconventional”

2. It is VERY difficult for those without knowledge of the art to understand. “As it is … part of a web of a dense web of linked ideas” He worries that “intellectuals, people who value ideas …somehow find this … idea impossible to grasp”. (Apparently therefore concluding they must be stupid, not for a moment that he may be wrong).

3. He feels those who oppose the concepts of free trade have an aversion to mathematics and mathematical models. He then goes on to refute an argument by Sir James Goldsmith against the validity of free trade ideas by telling us Goldsmith simply did not understand the “pauper labour fallacy”, which Ricardo dealt with “refut(ing) the claim that competition from low-wage countries is necessarily a bad thing” .

Krugeman does not bother to explain that further in the 1996 essay, but in a 2007 essay his own view towards that issue seemed to have changed: “But for American workers the story is much less positive. In fact, it’s hard to avoid the conclusion that growing U.S. trade with third world countries reduces the real wages of many and perhaps most workers in this country. And that reality makes the politics of trade very difficult.”

He concludes

“It’s often claimed that limits on trade benefit only a small number of Americans, while hurting the vast majority. That’s still true of things like the import quota on sugar. But when it comes to manufactured goods, it’s at least arguable that the reverse is true. The highly educated workers who clearly benefit from growing trade with third-world economies are a minority, greatly outnumbered by those who probably lose.

As I said, I’m not a protectionist. For the sake of the world as a whole, I hope that we respond to the trouble with trade not by shutting trade down, but by doing things like strengthening the social safety net. But those who are worried about trade have a point, and deserve some respect.”

http://web.mit.edu/krugman/www/ricardo.htm

LikeLike

A source for finding books.

This first link is to a search page which searches several dozen online booksellers.

http://used.addall.com/Used/

The second link is to the search for this book (How Rich Countries Got …) with prices ranging from $9 to $945.

http://used.addall.com/SuperRare/RefineRare.fcgi?start=0&id=161221015347360519&order=PRICE&ordering=ASC&dispCurr=USD&inTitle=How+Rich+Countries+Got+Rich+%85+And+Why+Poor+Countries+Stay+Poor&inAuthor=&exTitle=&exAuthor=&inDesc=&exDesc=&match=Y&exaTitle=&exaAuthor=

Enjoy

JW

LikeLike

Thanks, J, good links.

w.

LikeLike

I shall certainly buy the book, along with ‘Why Nations Fail” it sounds like an essential addition to any library.

I also thought about your point that manufacturing is more worthwhile or significant investing in than other areas of the economy because manufacturing investment produces greater products at a defined rate. That is true, but the other half of the equation is that you have to have the market. I am reminded of the coal industry. here in the UK and in the US. After WW2 substantial investments were made in the industry which improved production by huge amounts ( 10 fold in some estimations) This cut the workforce and resulted in a coal glut. Energy production diversified and with other factors resulted in the the coal mines being closed. I don’t think, despite the promises of Trump and the left wing leaders in the UK, that these coal jobs will ever re-appear, the world has moved on.

So investment in an industry, especially manufacturing does produce increased results, but is useful only as long as there is a market and at the right stage of technological process.

LikeLike

imo

Generating electricity, for the most part, should be either nuclear or coal but with as many hydro-dams as we can create which allows for the much needed control of fresh water.

Natural gas should not be just burned for heat. It should be saves for its many unique uses.

So, if they won’t go nuclear then the answer is coal.

LikeLike

I know I may get this wrong because it’s been a while since I studied it, but if one looks at the development of the Korean economy since the war there in the 1950s you will see that it moves through a series of stages.

I will over simplify the history by focusing on only a segment of the economy, but it goes something like this:

They started stitching shirts and did that until they could no longer compete with labor costs in SE Asia.

Then they imported fibers and manufactured fabrics and shipped them to the shirt stitchers.

As competition in fabrics increased, they started manufacturing fibers which they used domestically in the fabric business and exported the surplus.

And they built industry to develop inputs to fiber manufacture, and then refineries to feed the chemical industry, until they couldn’t go further up the value chain because they didn’t have petroleum resources domestically. But they did start oil companies that invested in production off shore.

It is true that the economy has always been strong in manufacturing, but they have not clung to the jobs dedicated to stitching shirts. Those jobs continue to circle the globe in search of low cost labor.

And without trade over this period Korea would not have developed as quickly as it has. Through out the period they were trading for low cost inputs to their stage in the value chain and exporting what they produced to stages further down the chain.

When they could not compete at the stage of the value chain they were at, they moved up to higher tech, higher valued activities — very often those requiring heavy capital investment and technical expertise that those further down the value chain neither could not afford, nor possessed.

It was a process of constant change and renewal driven by the need to be globally competitive and enabled by the free flow of materials in and out of the country (a.k.a trade).

The Korean economy today is 11th in the world in terms of output. It didn’t get there by hoarding gold or buying manufacturing inputs from higher cost domestic suppliers, or hanging onto jobs in industries where they could not compete internationally.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Pingback: True Wealth (h/t to Willis) | gwfenimore

I think this could be a poor long term strategy for oil. Besides living with more expensive energy, you’re using up your own supply.

LikeLike

TY Willis … really appreciated the summary … may even buy the book.

Much of the principles described are easy to understand when applied on a personally experienced level.

I still get amazed at the circle jerk justifications that are made by the people who typically benefit the most from a deviation from those basic principles.

LikeLike

“Here Hörnigk is cautioning against the very situation we have today, a huge trade deficit with the rest of the world. Bad idea.”

I disagree, not a bad idea. In Hörnigk’s day currency was universal, gold or silver. That has changed.

A trade deficit simply means you are getting more “stuff” than you are shipping. The US current account deficit is balanced by an equal and opposite US capital account surplus. (Unless your suppliers tuck the US$ you pay them in under their collective mattresses). And, guess what, this surplus is invested back in the US domestic economy, in productive assets and people (some object to this as well, but in the main most governments welcome FDI).

I don’t have time to research it now but that flat line BOT graph up until about 73/74 needs looking at since it would be extraordinarily coincidental for exports and imports to exactly balance every year…up until that time many countries balanced their current and capital accounts by jimmying their exchange rates…and some still do. In NZ we floated our dollar only in 1984. And even now there is a strong correlation between the international price of milk (our key export) and the NZ$.

I read recently that the only time the US has had a positive balance of trade was during the great depression, go figure.

On scalability

The digital revolution and new IP is even more scalable than manufacturing….as FB, Google et al demonstrate so vividly. And cheaper to deliver.

On Hörnigk’s last point you must remember that this was a time of turmoil, almost constant European warfare, with sieges, and blockades; it was strategically necessary to be as self sufficient as possible. One of the whole points of modern international trade is that it correlates strongly with peace. (you try not to damage countries that house your own factories and retail outlets). We’ve come a long way since then.

“For it would be better to pay for an article two dollars which remain in the country than only one which goes out, however strange this may seem to the uninformed.” I cannot see his reasoning for this assertion, and I believe it to be simply untrue today due to fiat currencies replacing gold and silver. (I also think it untrue as he says barter is OK, and money just enables the barter to be shifted in time). The dollar that goes out is used to buy from you, or is reinvested back in the economy

Whereas the dollar saved is kept in the country and invested in other things jobs etc. This is the huge advantage of trade (and innovation).

So far colour me unconvinced

Cheers,

B

LikeLike

The most important issue is not so much the economic one, but the social one. Probably a totally automated economy would be extremely efficient, but the social cost would be disastrous. The solution is to find the compromise.

LikeLike

Agree.

One wonders how 7B people are supposed to earn an honest living?

We can’t mow each others lawns and clean each others houses.

We can’t all work in the exciting world of the fast food industry.

LikeLike

We move already in that direction of surplus in manpower. We see demographic problems in Europe, the southern countries can’t generate the necessary jobs to reduce the high unemployment rate.

LikeLike

Some thoughts by Churchill, as related by Steve Hayward:

http://www.powerlineblog.com/archives/2016/12/the-question-of-trumps-consistency.php

Tactics and strategy may change dramatically in pursuing an unchanging objective.

LikeLike

I would reiterate that my only point relevant to the discussion was what measure to use to reflect the health of manufacturing was “that the metric for the health of the sector should NOT be employment,” which is in no way addresses the main thesis above. In fact the views of another rather famous statesman famously went from strongly free trade to much more protectionist. From a biography of the man we find: “In one of the great somersaults of his career, he turned himself into a vigorous advocate of protectionism. He even adopted the most controversial aspect of the protectionism programme, which he had regularly denounced since 1903: food taxes.” [Churchill: The Unexpected Hero by Paul Addison]. Churchill himself wrote about consistency in politics in an essay [cleverly titled “Consistency in Politics”] that: “A distinction should be drawn at the outset between two kinds of political inconsistency. First, a Statesman in contact with the moving current of events and anxious to keep the ship on an even keel and steer a steady course may lean all his weight now on one side and now on the other. His arguments in each case when contrasted can be shown to be not only very different in character but contradictory in spirit and opposite in direction: yet his object will throughout have remained the same. His resolves, his wishes, his outlook may have been unchanged; his methods may be verbally irreconcilable. We cannot call this inconsistency. In fact it may be claimed to be the truest consistency. The only way a man can remain consistent amid changing circumstances is to change with them while preserving the same dominating purpose.”

LikeLike

Willis,

It seems to me that the common denominator for this discussion is Walmart. Walmart seeks (despite the founders’ stated goals so many years ago) to buy every good at the cheapest price. Most americans, through advertising and greed, have come to accept the premise that cheapest is best no matter how poor the quality. Most are not willing to pay more for better quality or better service.

I remember well the demise of Niataka Nursery in a nearby town. The man who owned it had a University of California degree in horticulture. I witnessed with my own eyes those who would come to him for advice and then drive a few blocks down the street to the big box store to buy a product they could have bought from the nursery for slightly more money. And so we lost a valuable resource to the lowest price meme, but at a high cost to the community.

And the follow on to the cheap and cheaply made junk from all the big box stores? Storage units by the thousands filled with junk from somewhere. I appreciate your efforts to educate the masses…but I’m not going to hold my breath.

pbh

LikeLike

Thanks, McComber Boy. You say:

I don’t hold my breath, but on the other hand, I’d rather light a candle than either curse the darkness or just sit quietly in the dark …

w.

LikeLike

“Most are not willing to pay more for better quality or better service.”

One problem with that thought is that paying more doesn’t that mean you get a better product or service but, I totally agree with your concern of the high cost to community.

But, is either Socialism or Protectionism the answer to this?

LikeLike

The trade deficit is only looking at half the picture.

If we trade dollar bills for imported manufactured goods, we get things we want, and they get pieces of paper.

They don’t stuff the pieces of paper under their mattress — the money is borrowed by people who want to borrow US dollars.

The biggest customer borrowing US dollars from abroad is the US government.

Shut down the trade deficits and the US government is going to have to borrow a lot more money from US citizens and/or raise taxes.

Two sides of trade; Things and capital.

Obama was a master at deficit spending.

Trump’s promises, if kept, could beat Obama on deficit spending.

Those federal budget deficits are financed with a lot of borrowing from abroad — capital flows are the other side of trade flows that few people see (look up Balance of Payments).

Hawaii has about 640,000 jobs — less than 2% are manufacturing jobs.

They seem to be doing well with little manufacturing.

LikeLike

Pingback: True Wealth | Skating on the underside of the ice | Cranky Old Crow

Pingback: How Rich Countries Got Rich | Skating on the underside of the ice

It’s not just manufacturing anymore either. Chicken feed and orange juice from Brazil? Yup. https://www.firstthings.com/web-exclusives/2017/01/my-orange-juice-came-from-brazil

LikeLike

Pingback: The Economic Cost of the Social Cost of Carbon | Skating Under The Ice

Pingback: The Economic Cost Of The Social Cost Of Carbon | Watts Up With That?

Pingback: Economic Cost Of The Social Cost Of Carbon | US Issues

Pingback: Who Benefits From Free Trade? | Skating Under The Ice